Gamebooks and grammars

It was years before my first computer. Even longer before I could even dream of having a real-life gaming group. Gamebooks were my first taste of fantasy roleplaying, and I loved them to pieces. Sometimes literally, to my eternal shame. Here was a kind of book that didn't just sit there waiting for my imagination to kick in, but actively invited me to explore the story! Not only that, but it even winked at me complicitly, and played with the way people read.

I promptly tried to write my own, as you might expect. It got surprisingly far considering I was twelve.

Wait, what's a gamebook? Turns out, most people know them as Choose Your Own Adventure instead, CYOA for short, after the name of a hugely popular book series in the 1980s. Those however only offered branching paths. Once the genre crossed the pond to Europe, it quickly acquired RPG rule systems that allowed people to actually play through an adventure, dice rolls and all. A means to experience the joys of fantasy gaming our own way, come to think of it.

(Beware that Choose Your Own Adventure is a trademarked phrase whose owners actively defend it in 2019. Stick to using the abbreviation to stay safe.)

For a while, the medium died out as videogames took over. More recently however, as interactive fiction returned in force, so did gamebooks. People even write the traditional, printed kind again!

However, I'm more interested in those modern gamebooks that take advantage of a computer. Not only to roll the dice for you, though that's a bonus, but also to do things that would be tricky or at least clumsy to pull off in the analog world. Such as shuffling events around to present the reader with a different challenge every time: a must if I am to play my own games. My early attempts at encounter-based game design, as I named it nearly two years ago, weren't so great. But in the mean time, an explanation and solution presented itself.

You see, it's hard to make a compelling narrative by shuffling a deck of cards. Guess that's why tarot reading is an art. Even with fancier algorithms, random is random, and narratives are like music: they need a little structure. No, seriously. Ever heard of a story beat? It's not a perfect analogy, but a story too needs a succession of highs and lows arranged so as to form a pleasant rhythm. In music, it may be something like "low, lower, high, low", while a narrative goes "setup, escalation, conflict, conclusion". In both cases this structure repeats fractally from the overall work to each of its parts. And in both cases there are rules for what notes may follow each other.

These rules form a grammar.

Ironically, I was pushed towards this realization after the card deck metaphor proved tricky to implement with SugarCube 2 markup. I could have forced the issue (there has to be some way to do it in Javascript), but it would have meant going against the grain, which to me is a big fat warning sign. Instead, I took a step back and tried to remember what kind of game it was supposed to be in the first place. Namely, a good old dungeon crawl.

Now that's a formulaic genre, to say the least.

Once that became clear, it wasn't hard to come up with the current structure: you follow a corridor; it can lead to some sort of obstacle to overcome, or a room to search for something useful. Poke around enough, and you'll attract a wandering monster. Which in turn will have a lair nearby, with treasure in it. And after each challenge, there's a moment of respite that you can use to replenish your reserves before moving on.

Within this framework, there's plenty of room for variations, and even improvisation. You'll want to gradually raise the stakes, but also to ease up the tension now and then. To suggest a progression, yet make your audience forget the time. It's still an art, and randomized elements aren't going to be nearly as good as handcrafted details. They do, however, require strategy, as opposed to memorizing patterns. Not that memorizing patterns can't be fun: think Chess openings, or bullet hell shoot'em ups. It's just not what I want my games to rely on.

Right. Grammars. Maybe you've heard how every good journalistic piece must answer the so-called "five Ws": who, what, when, where, and why. Interestingly enough, so must any sentence. You can't very well have a valid one without the "who", i.e. the subject, and the "what", better known as a predicate. One or the other may be implied, if you have the context, but it still has to exist. Likewise, a story needs a "who" (the main character) and a "what" (the plot), which in turn begs for a "why" (the premise). So does each part or chapter taken by itself.

Now you can see why I was talking about fractal structures. Which grammars are famously good at describing.

Why all this talk about narrative structure? In static fiction, you can just wing it. In a graphical RPG, you can give players a map to explore as they like, and call it an open world. But in a gamebook, structure is everything. Passages and choices carry all the weight. Pacing and flow; how interactive and replayable it is; average length of a playthrough. All of that you have to put in on purpose. Even if it's the computerized kind, where certain parts are randomized and/or repeated.

Early results are very encouraging. The game is a pleasure to work on, ideas keep coming thick and fast, while people are praising the various prototypes. It remains to be seen how well the paradigm I described above will work out by the end. Still have a long way to go, and there are many branching paths between here and there.

Get Keep of the Mad Wizard

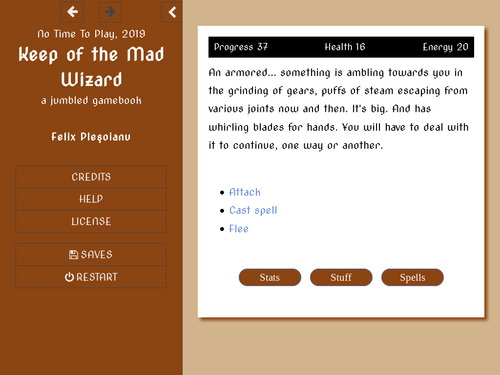

Keep of the Mad Wizard

a jumbled gamebook

| Status | Released |

| Author | No Time To Play |

| Genre | Role Playing |

| Tags | Dungeon Crawler, Fantasy, Monsters, Short, Text based |

| Languages | English |

| Accessibility | High-contrast |

More posts

- Musings on combat in videogamesApr 16, 2019

- Dungeon crawls and simple pleasuresApr 10, 2019

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.